PAUL WELLER: OUR GREAT POET OF ALIENATION

By Duncan R. Shaw, PhD

Madrid, 12 August 2022

How gratifying it is to open the eyes of young people to a twentieth century musician, artist, writer, philosopher, decent politician (rara avis, to be sure) – somebody they’d never really heard about properly, despite the internet.

Having a big screen and internet in the classroom obviously helps: to quickly show them such giants as George Gershwin, Olof Palme, Paul Robeson, Dylan Thomas, David Lange, David Hockney, Maxim Gorky, Victor Klemperer, Malcolm Lowry, Roland Orzabal, Lasse Hallstrom, Kurt Vonnegut, Iris Murdoch, Scott Joplin, Raul Alfonsin, Jackson Pollock, Ettore Scola, Woody Guthrie, Gunter Grass, Sean O’Casey, Thomas Pynchon, Sam Cooke, Ricardo Lagos, Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, Jackson Browne, JD Salinger, Doris Lessing or Joe Strummer…

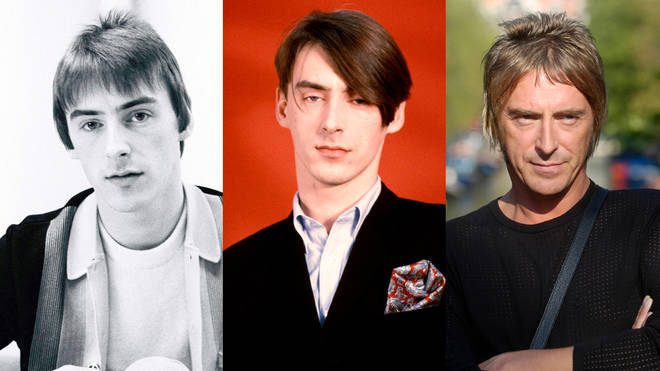

Two weeks ago I called Strummer ‘Our Great Poet of Protest’. Today I want to focus on the man I consider to be England’s other great late twentieth century poet: Paul Weller, creator of The Jam and The Style Council, rock icon today – ‘The Modfather’.

Paul Weller: ‘Our Great Poet of Alienation’, the teenager (born 1958, in suburban Woking) who sang to my generation about our daily frustrations and satisfactions: girls, clothes, music, politics…

Like Strummer, Weller is quintessentially English. Neither of them had the stomach or patience to ‘break America’, both of them loathed the gung-ho, aggressive, materialistic USA of the Reagan years.

Not that Strummer (six years older) and Weller saw eye-to-eye to begin with. The black-suited, Union Jack-sporting Jam looked so incongruous on tour with the scruffy Clash and Sex Pistols in 1976. Strummer laughed about The Jam’s ‘Burton suits’ and the 18 year-old Weller, ever the contrarian, said The Jam were Mods not punks – and would be voting Conservative.

Inevitably, Weller and Strummer eventually became friends – birds of a feather stick together. They wrote about similar things: political corruption, inequality, the British class system, revolution, alienation…

Weller deftly moved on from the glowing childhood nostalgia of Tales From the Riverbank to the alienated anger of Eton Rifles, written after seeing the well-fed boys of the infamous private school jeering at a protest march of unemployed northerners passing through Eton on their sad way to London.

Forty years after Eton Rifles, Weller flew into a rage when told that old Etonian Prime Minister David Cameron loved the song.

“The whole thing with Cameron saying it was one of his favourite songs… I just think, ‘Which bit didn’t you get?’…It wasn’t intended as a fucking jolly drinking song for the cadet corp.”

The ascent to power of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 made Weller’s song writing sharper, angrier – more ‘political’. Not that songs like Town Called Malice (a Dylan Thomas-esque portrait of a small English town hit by Thatcherism) were without lyrical elegance: “Better stop dreaming of the quiet life Cause it’s the one we’ll never know And quit running for that runaway bus ‘Cause those rosy days are few And stop apologizing for the things you’ve never done ‘Cause time is short and life is cruel but it’s up to us to change This town called Malice Rows and rows of disused milk floats Stand dying in the dairy yard And a hundred lonely housewives clutch empty milk Bottles to their hearts Hanging out their old love letters on the line to dry It’s enough to make you stop believing When the tears come fast and furious In a town called Malice Struggle after struggle, year after year… A whole street’s belief in Sunday’s roast beef Gets dashed against the Co-op To either cut down on the beer or the kids’ new gear It’s a big decision in a town called Malice…”

Weller’s lines about ordinary people battling to get through to the end of the month (“Struggle after struggle, year after year…”) – so reminiscent of Lennon and McCartney, Ray Davis and Morrissey – are just as relevant today, with inflation and the ‘heat or eat’ dilemma.

He did well to reject the silly ‘spokesman of a generation’ label, like Guthrie, Dylan and Lennon before him.

Weller’s sharp understanding of working-class existence hit a new peak with That’s Entertainment, written in a drunken hour back in his barren flat after eight pints of Watney’s Red: “Days of speed and slow time Mondays

Pissing down with rain on a boring Wednesday

Watching the news and not eating your tea

A freezing cold flat and damp on the walls…”

By this time Weller felt rather constrained in The Jam; he wanted to experiment with jazz, funk, soul, blues, Motown, and realized that old schoolfriends Bruce Foxton and Rick Butler should be consigned to the past.

So in 1982 he broke up the most successful band in Britain, in order to start The Style Council: a revolving circus of admiring young musicians as sharply dressed as Weller, all of them eager to follow his every whim and fad.

Within a year he had constructed a band almost as popular (and lucrative) as The Jam, against all the odds and dire predictions of failure.

(Weller has been offered countless millions to reform The Jam but has resolutely refused – like his friend Noel Gallagher with Oasis).

I loved TSC even more than The Jam – which is really saying something. Image, clothes, poise, politics, jazz, soul, blues – The Style Council had it all, including the biggest and most relevant album of 1985, which I would listen to endlessly (on my Sony Walkman) while hitching a ride on the highways of Europe, America and Australia, or while walking alone down the Andes (all the way from Colombia to Argentina).

My mind goes a blank, in the humid sunshine

When I’m in the crowd I don’t see anything

I fall into a trance, at the supermarket

The noise flows me along, as I catch falling cans

Of baked beans on toast, technology is the most

They struggle hard to set themselves free

And they’re waiting for the change…”

An excellent musician and singer! The Jam was one of my favorite groups.

Hope your article help to open the eyes of young people to such an important artist.

Thanks Professor. Another warm tribute to one of the most important bands of my youth and the storyteller Weller. The Jam were my favourite band in 1978 to 79 but I have to admit to losing interest by the time of The Style Council and then reconnected for some of the Modfather years! Weller's early promise was summed up in two tracks from their first 1977 album; In the City and Away from the Numbers. After stumbling with second album This is the Modern World, Weller took inspiration from the 1960s' greatest writer of Kitchen Sink vignettes, Ray Davies of the Kinks. Weller's next album All Mod Cons was where it all came together, and was not really surpassed by anything the Jam subsequently did, although Setting Sons came close and the classic single Going Underground still stands alongside Eton Rifles as amongst their best. All Mod Cons though had light and shade from the wistfully romantic English Rose,

which he appears embarrassed about as it gets no sleeve credit, to the gritty and angry Mr Clean, In the Crowd, and finally, his masterpiece of storytelling, Down in the Tubestation at Midnight, where our honest Joe is beaten up by thugs whilst taking a curry back to his wife....'they took the keys..she'll think it's me' as he lies in a pool of blood. Yes, Weller captured that need to challenge the status quo that the corporate world ties us into and search for that secret place covered in moss and colourful flowers 'The Place I Love' that is a million miles away. The mellowing of his later years means he either found it, or gave up trying and accepted hard reality. He tried at least, and encouraged us to do so too!

Another good article: thanks. You’re right to observe that we are living in similar times to when ‘Town Called Malice’ was mined. I wish you a young an engaged future readership!

Duncan Shaw's column continues to shine with his nimble and synthetic touch upon the keyboard. Like all his previous pieces, this one is a summary of one of the innumberable conversations in the long chain of our 25 year dialogue during which Duncan has summarized a reading list that I (nor anyone else) could ever actually get through, cover to cover. So praise to the great summarizer of contemporary history, our brother with the memory of iron and the imagination of a wanderer and a student of story....

I was at the Jam's final concert in Brighton at the end of 1982. I went with my friend from Minehead and flatmate at the University of Sussex's East Slope, Andrew Mansi (later of Mute Records fame, his association with Vince Clark, the Basement Jacks, among many others, and beyond). It was the fifth and final Jam concert I was personally witness to, and only his second. He liked and admired the Jam and Paul Weller in particular, but he was far more drawn to Strummer and the Clash. I could not decide between them, and I am not sure that I ever have. I understand to draw of the Clash, but I also understand Weller's particular expression of the alienation that came from an early but distinct phase in breakdown and commodification of the British middle and working classes. He had a slightly different youth experience from Strummer et al and his voice, his music, his poetry, his art are distinct but also very much socially blooded related.

In addition to Town Called Malice, That's Entertainment, etc. I would draw attention to the Jam songs that Mansi introduced to me during the time we shared together in Britain (or whatever you would prefer to call it: see Dr. Davies's book, The Isles, to go deeper into the quagmire of the historical, geographical and political puzzle of 'that place's' name). First, A-Bomb in Wardour Street and Going Underground, two anthems from those long ago days....

I only saw The Jam once, not long after they released their first single In the City. They were playing a student union gig at London University, near the British Museum, if memory serves and wearing scowls and what appeared to be school uniforms. Such energy! The only other live acts I've seen with the same energy were The Who (with Moon) and Doctor Feelgood (before they succumbed to demented squabbling).

The dynamism was the USP - and apparently on offer any time, any place. Danny Baker says he saw them once play an empty hall in Amsterdam and Weller still gave it both barrels: roaring at the empty room.

I depart from Duncan slightly on Paul's post Jam work. Like him I loved The Style Council and played Long Hot Summer a gazillion times, though I was never convinced by him and Mickey Talbot as English gondoliers in the video. Later the spell faded - perhaps partly because of Paul's sometimes grandiose public statements - Mark E Smith of The Fall called him the Bard of Woking - unkind but Smith had a point.

The main problem though is while Weller often displays excellent taste, I'm not sure that he adds much musically to the artists he emulates. I'm very grateful that he introduced me to Anita Baker via his version of Angel - but I'd now rather listen to the original. Partly it his voice - for me its a bit limited, especially when compared to others ploughing a similar furrow: Michael McDonald, Robert Palmer etc. So my Weller playlist is confined to that glorious run of singles from 1978-82.

I loved this article because it captures the essence of the era perfectly, I loved learning more about The Jam and The Style Council and the bad boys of British music. Thank you, Professor Shaw!